Snowdrops in Art History & Literature

“The Snowdrop” (accompanied by purple and yellow crocuses), a plate from “The Temple of Flora,” the third and final part of Robert John Thornton’s New Illustration of the Sexual System of Carolus von Linnaeus (1807). Image Source: Missouri Botanical Garden via Internet Archive

Although winter may seem dormant, it holds quiet beauty in resilient blooms. Chief among January’s flowers are snowdrops (Galanthus spp.), with their pristine white petals and nodding heads symbolizing hope and renewal. Tougher than they appear, these understated flowers have been featured in art and literature for centuries, celebrated for both their botanical charm and symbolic significance.

Renaissance Art: Religious Symbolism and Early Snowdrop Studies

Snowdrops hold deep Christian symbolism, linked to the Virgin Mary and Christ’s crucifixion. Their white petals signify Mary’s purity, and their drooping heads suggest humility and mourning. Known as "Candlemas Bells," they are said to have first bloomed on Candlemas, symbolizing purification and faith. Emerging in winter, they evoke renewal and resurrection—echoing Christ’s triumph over death.

Snowdrop (Galanthus nivalis) with a fly, Folio 27 from Book of Flower Studies, c. 1510–1515, Master of Claude de France, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Cloisters Collection, New York

This symbolism appears in religious art, notably in the Book of Flower Studies (c. 1510–1515) by the Master of Claude de France. On folio 27, snowdrops open gracefully beside a blue fly, reflecting early naturalistic detail. Created during the last great phase of northern manuscript illumination, this work captures the flowers’ beauty not just for their meaning, but as studied, living forms.

"Portrait of Raja Bikramajit (Sundar Das),” Folio from the Shah Jahan Album, recto: ca. 1620; verso: ca. 1540, Painting by Bichitr Indian; Calligrapher Mir 'Ali Haravi, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Renaissance also marked a growing interest in botany; snowdrops became subjects of early botanical studies. Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues’ Snowdrops and Painted Lady Butterfly (c. 1568) is a prime example, blending art and science in a composition that arranges three snowdrops beneath a painted open-winged lady butterfly. This work highlights not only the structure of the flower but also its symbolic ties, as both the butterfly and the snowdrop were often associated with death and grief. Snowdrops’ natural appearance in graveyards, tilting their heads like little mourners, has long evoked a sense of respectful sorrow.

Snowdrops and lady butterfly, watercolour, by Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, French School, about 1575. Museum no. AM.3267H-1856. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Baroque and Dutch Golden Age: Still Life Elegance

During the Dutch Baroque era of the 17th century, snowdrops often appeared in intricate still-life paintings, particularly in floral compositions. These works, celebrated for their astonishing detail and symbolic depth, showcased snowdrops as both botanical curiosities and visual metaphors. While snowdrops were relatively common in Europe, their careful inclusion in still-life bouquets often carried layers of meaning, reflecting the cultural, scientific, and artistic interests of the time.

A snowdrop tucked among a tulip and a rose. Bouquet in a Clay Vase [detail], c. 1609, Jan Brueghel the Elder, The National Gallery, London

Dutch still lifes frequently combine flowers from different seasons in a single composition. Snowdrops, which bloom in late winter, were juxtaposed with tulips, irises, roses, and summer blooms, creating striking "season-defying" bouquets. This practice was not intended to depict reality but rather to demonstrate the painter’s skill and the patron’s wealth, as acquiring and cultivating such an array of flowers required significant resources.

These paintings often reminded viewers of the transience of life, underscored by the ephemeral beauty of flowers. Snowdrops, with their short bloom time and delicate form, reinforced these messages of mortality and renewal.

Large bouquet of flowers in a wooden container, around 1606/1607, Jan Brueghel the Elder, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna. Can you spot the snowdrop?

[Detail] Large bouquet of flowers in a wooden container, around 1606/1607, Jan Brueghel the Elder, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna

Snowdrops in the Enlightenment: Art, Science, and Discovery

The Enlightenment (17th to 18th centuries) was a time of deep fascination with the natural world, driven by advancements in science and the burgeoning field of botany. Snowdrops (Galanthus spp.), with their delicate blooms and ability to flower in the coldest months, captivated both scientists and artists alike. Botanists documented snowdrops in taxonomies inspired by the work of Carl Linnaeus, noting their resilience and unique adaptations, such as their antifreeze proteins and thermotropic tepals, which protected their pollen from winter’s harsh conditions.

Single snowdrop (Galanthusnivalis), collage, 1777, Mary Delaney, © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Mary Delany (1700–1788), an influential artist and naturalist of the Georgian era, created her renowned Flora Delanica, a collection of over 1,000 paper mosaics depicting flowers with stunning detail and scientific accuracy. Among these, her depiction of snowdrops highlights their natural elegance and precision, reflecting the Enlightenment’s emphasis on observation and classification. These collages were celebrated for their innovative approach, blending scientific curiosity with artistic expression, and remain a valuable historical record of 18th-century botany.

Snowdrops also symbolized hope and renewal, themes that aligned with the Enlightenment’s ideals of progress and discovery. Their quiet beauty and early blooming in harsh conditions became metaphors for resilience and the transformative power of knowledge, cementing their place in the art and science of the period.

Snowdrops in the Victorian Era: Romanticism, Obsession, and Sentiment

By the 19th century, snowdrops had become cherished symbols of Romantic and Victorian sentiment, embodying hope, renewal, and life's cycles. Their delicate resilience aligned with Romantic ideals of nature’s emotional power. William Wordsworth captured this in To a Snowdrop (1819), calling it a “venturous harbinger of Spring” and a “pensive monitor of fleeting years,” reflecting nature’s beauty, transience, and human endurance.

To a Snowdrop

‘Lone Flower, hemmed in with snows and white as they

But hardier far, once more I see thee bend

Thy forehead, as if fearful to offend,

Like an unbidden guest. Though day by day,

Storms, sallying from the mountain-tops, waylay

The rising sun, and on the plains descend;

Yet art thou welcome, welcome as a friend

Whose zeal outruns his promise!’

-William Wordsworth personifies the flower in his sonnet To a Snowdrop (1819)

Costume design by Wilhelm (Charles William Pitcher, 1858-1925) for 8 Snowdrops - Little Children in the Bell Flower Ballet in the pantomime Dick Whittington as performed at Crystal Palace on 24th December 1890, © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

As the Victorian era advanced, snowdrops moved from poetic and theatrical muse to botanical obsession. Horticultural advances led to galanthophilia—the passionate collecting of rare snowdrop varieties. Mass plantings created striking winter displays, signaling spring’s approach. In floriography, they symbolized hope, purity, and mourning, often featured in graveside plantings, floral tributes, illustrations, and decorative arts for their quiet elegance and emotional resonance.

An 1830 drawing of young woman wearing a fringed cloak and pale gown, standing facing front, hair dressed up with a snowdrop, gesturing to the right towards pots of snowdrops on a window-ledge beside her, by John P Quilley © The Trustees of the British Museum

Art Nouveau and the Decorative Arts

The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Art & Architecture Collection via New York Public Library Digital Collections

Art Nouveau (approximately 1890–1910) was an international art and design movement characterized by its flowing, organic lines and celebration of natural forms. Snowdrops were a perfect match for this aesthetic due to their delicate, arching stems, drooping flowers, and understated elegance. The movement sought to integrate art into everyday life, and floral motifs, including snowdrops, featured prominently in everything from architecture to ceramics, textiles, and jewelry.

A prominent Art Deco designer, Maurice Pillard Verneuil featured snowdrops in his 1896 publication La Plante et ses Applications Ornementales, transforming their natural form into stylized floral patterns. Known for bold motifs in ceramics, wallpapers, and textiles, he drew inspiration from Japanese art and nature—especially the sea—highlighting the snowdrop’s versatility in decorative design.

Snowdrops and Violets, 1903, Eva Francis, Touchstones Rochdale, Rochdale England, Rochdale Arts & Heritage Service

Snowdrops in Modern Culture and Design

In contemporary culture, snowdrops retain their traditional symbolic meanings of hope, renewal, and purity, while expanding to embody themes of sustainability and environmental resilience. Their early bloom in winter serves as a metaphor for enduring challenges and heralding brighter days, making them a source of admiration and inspiration across various creative fields. Whether in fine art, fashion, architecture, or digital design, snowdrops continue to adapt to changing trends and technologies, underscoring their enduring appeal as both a natural wonder and a powerful symbol of resilience and beauty in the modern world.

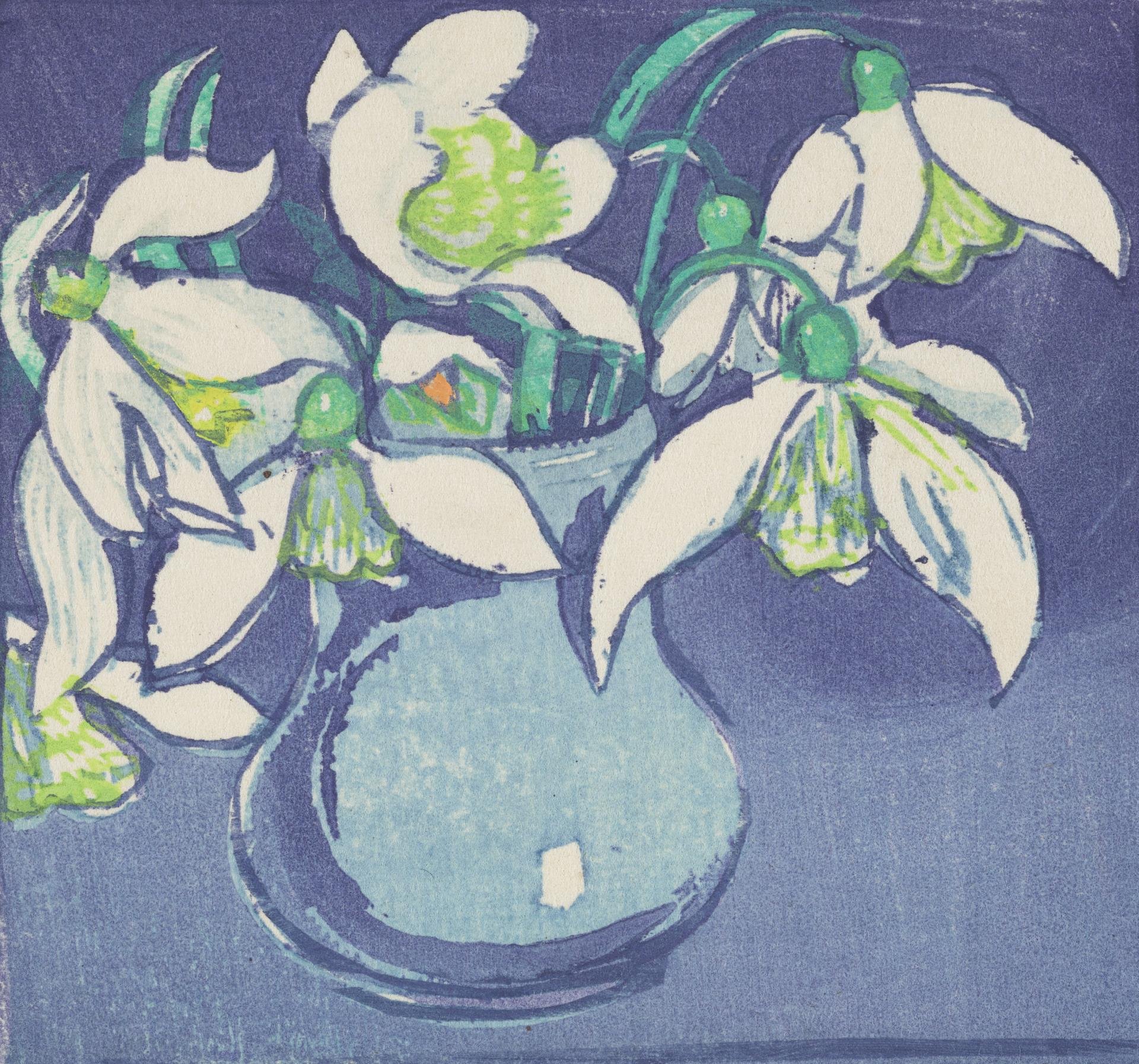

Snowdrops, color woodcut on paper, 1935, Mabel Royds,National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

The Science Behind Snowdrops: Nature’s Winter Champions

Snowdrops (Galanthus nivalis) are more than just delicate winter blooms—they’re a testament to nature’s ingenuity and adaptability. Native to Europe and parts of the Middle East, they flourish in temperate woodlands, meadows, and riverbanks. Their natural range extends from the British Isles and Central Europe to the Balkans, Turkey, and the Caucasus.

The genus Galanthus includes around 20 recognized species, but within those species, there are thousands of cultivated varieties (cultivars). These varieties, often developed for their unique markings, sizes, or bloom times, make snowdrops a favorite among gardeners and collectors. Notable examples include Galanthus nivalis (common snowdrop), Galanthus elwesii (giant snowdrop), and Galanthus plicatus (pleated snowdrop).

Enthusiasts, known as galanthophiles, prize rare cultivars such as:

‘Magnet’: Known for its gracefully arching flower stalks.

‘Green Tear’: A highly sought-after variety with distinctive green markings on its inner petals.

‘Lady Beatrix Stanley’: A double-flowered snowdrop prized for its intricate petal structure.

Delicate but resilient snowdrops emerge through the frost-kissed earth on a chilly winter morning. Image Source: Unsplash

Indeed, snowdrops are scientific marvels. They survive frost with antifreeze proteins and push through frozen soil to bloom early. Their tepals close in cold and open in warmth to protect pollen and attract bumblebees. Though pollination is rare, they spread by bulb division and ant-assisted seed dispersal. Their bulbs also yield galantamine, used in Alzheimer’s treatment.

Snowdrop Traditions and Festivals in Britain

In Britain, snowdrops have long been cherished as a symbol of hope and the promise of spring. These delicate flowers are often called Candlemas Bells because they bloom around Candlemas (February 2), a Christian holiday commemorating the presentation of Jesus at the temple. Their pristine white petals symbolize purity and renewal, and they were often planted in churchyards and along monastery grounds in medieval times.

In modern Britain, snowdrop collecting has grown into a niche hobby called galanthophilia. Rare varieties like Galanthus ‘Lady Beatrix Stanley’ or Galanthus ‘Green Tear’ can fetch hundreds of pounds among enthusiasts.

Snowdrops in the morning sunlight at Anglesey Abbey, Cambridgeshire, England. Image Source: National Trust Images/Justin Minns

Snowdrop Walks and Festivals

Today, snowdrop walks and festivals are a beloved British tradition, drawing visitors to gardens and estates across the country during winter. Some notable events include:

Anglesey Abbey Snowdrop Festival (Cambridgeshire)

One of the most famous snowdrop events, Anglesey Abbey, boasts over 500 varieties of snowdrops planted in stunning drifts across its landscaped grounds, many rare. Visitors stroll through woodland paths and enjoy the serene beauty of these early blooms.

Painswick Rococo Garden (Gloucestershire)

Known as one of the most enchanting places to see snowdrops, this 18th-century garden features over five million snowdrops carpeting its whimsical, historic grounds.

Snowdrop Valley (Somerset)

A picturesque hidden valley in Exmoor National Park, Snowdrop Valley transforms into a winter wonderland in February, with wild snowdrops carpeting the forest floor. This natural display offers a more rustic and untouched beauty.

Welford Park (Berkshire)

Famous for its magnificent snowdrop walks, Welford Park’s displays line the banks of the River Lambourn, creating breathtaking reflections. The site even inspired the snowdrop scene in the 2015 movie Far from the Madding Crowd.