Ruff-ing It

Syndics of the Amsterdam Goldsmiths Guild, 1627, Thomas de Keyser, Toledo Museum of Art, Public Domain via WikiCommons

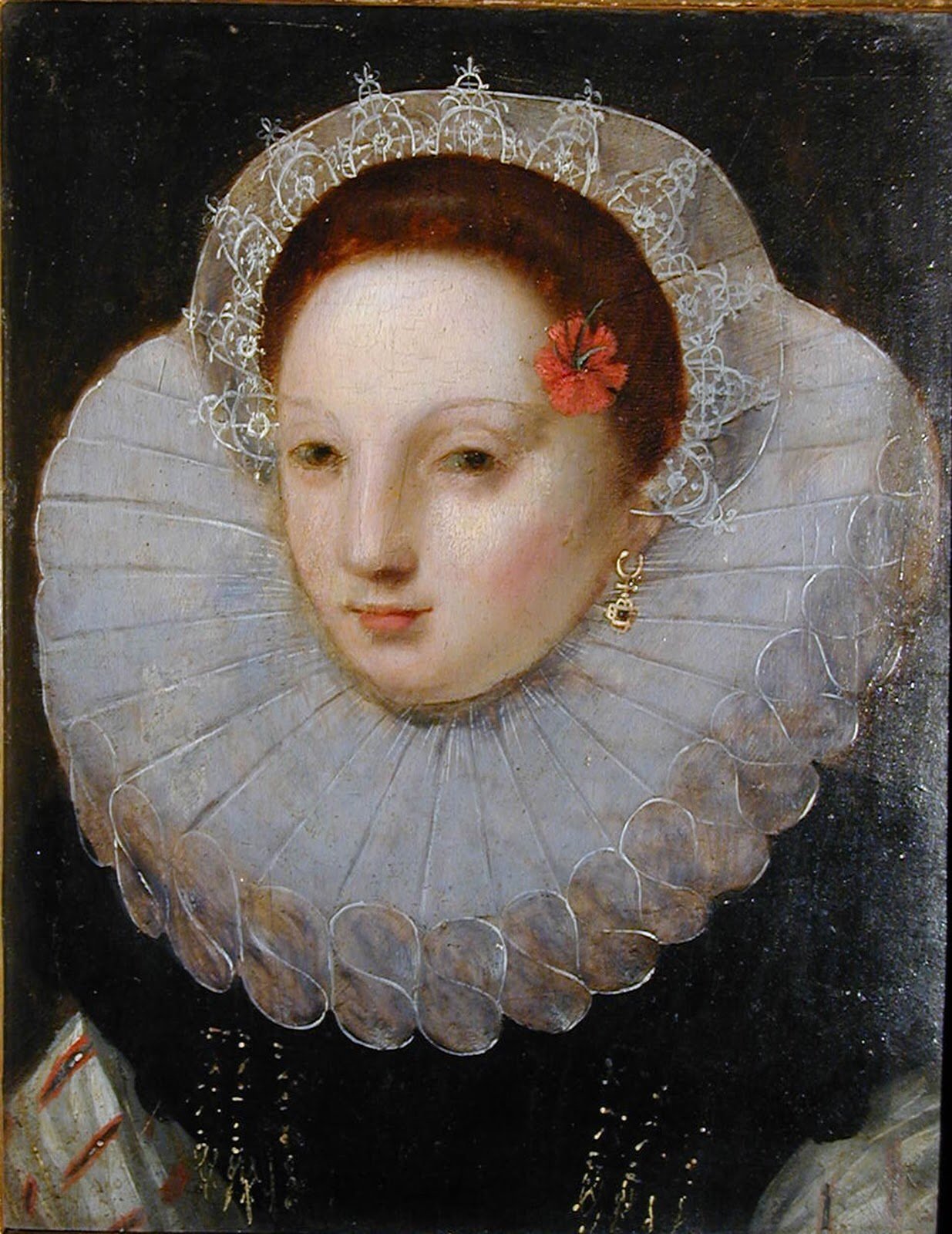

The ruff is a crimped or pleated collar or frill, usually wide and full. And white. It was an iconic fashion statement in Europe from the mid-16th century into the 17th century. Artists of the period delighted in portraying how the light fell through the fine and near-transparent linen, how the pleats repeated endlessly. As such, portraits of collared men, women, even children adorn the halls of museums all over the world.

But ruffs aren’t just a thing of the past. They continue to fascinate and can be seen on the fashion runway year after year.

So, why bother with this crazy wild accessory? What’s the story?

Balenciaga, Spring 2006 Ready-to-Wear Collection, Vogue Magazine

Today, we’re most familiar with the large cartwheel ruff popular in Elizabethan England and 17th-century Dutch portraiture.

Elizabeth I (Armada Portrait), 1588, Anonymous, formerly attributed to George Gower (1540-1596), Woburn Abbey, UK, Public Domain via WikiCommons

However, this large, fancy ruff evolved from a less grandiose application dating back to the late 1400s.

During the Renaissance, the necklines on men's doublets—slightly padded short overshirts—opened to reveal the shirts worn underneath. These shirts were often closed at the neck by means of a draw-string laced through the edge of the fabric. When such a string was drawn tight, it produced a gathered ruffle around the neck and added a little visual interest to the outfit.

Man with a Glove, 1520, Titian, Louvre Museum, Paris, Pubic Domain via WikiCommons

The Tailor, from 1565 until 1570, Giovanni Battista Moroni, National Gallery, London, Public Domain via WikiCommons

This ruffle soon became fashionable, and by the mid-sixteenth century, it grew in size until it became a separate piece of cloth or lace that was tied around the neck. The first wide ruffs appeared in Spain, but they soon spread to England, France, Italy, and Holland, where they remained popular well into the seventeenth century.

These independent, interchangeable pieces of fabric served a practical purpose at first, keeping garments clean at the neckline. The ruffs could be laundered separately, saving the time and cost of cleaning an entire outfit. Even as they became popular as decorative accents and not just for their functional qualities, early ruffs had modest dimensions.

Queen Elizabeth of Valois, third wife of Philip II, 1605, Juan Pantoja de la Cruz, Museo del Prado, Madrid, Public Domain via WikiCommons

Archduchess Katharina Renea (1576-1595), c. 1591, Jakob de Monte, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna, Public Domain via WIkiCommons

Then, in 1564, the introduction of starch to England from the Low Countries facilitated a marked expansion in the size of ruffs. By enhancing earlier ruffs made with just wire, ruffs evolved into large, elaborate markers of wealth and ostentation.

From 1580 to 1610, the ‘cartwheel’ ruff was all the rage, comprising up to six yards of material, starched into up to 600 pleats, and extending eight to twelve inches from the neck. The thinner and finer the linen used, the more money you would have spent on it. The incredibly fine fabric had to be pleated into hundreds and hundreds of pleats, starched and set into perfect cartwheel folds and kept clean. Hours were spent looping, ironing, and starching lace and linen into place. Embroidery, jewels, and precious metals were added to heighten the glamour of the ruff. They could take hours to set and had to be preserved by servants in special boxes.

Yet, most often ruffs could only be worn once as body heat and the weather would cause it to droop and loose shape.

Wearing a stiffened, starched ruff was equally high maintenance as making and storing it. The ruff now forced the wearer to keep their chin up and assume a proud and haughty pose. It was impossible to eat without special, long utensils or do any sort of regular activity.

The starch used on ruffs could be dyed yellow, blue, or green, but white ruffs continued to be most common. Blue dye was sometimes used to emphasize a pale complexion, which was fashionable at the time. In England, the Puritans rightly considered ruffs a vanity project and dubbed starch “the devil’s liquor.”

By the late 16th century, what was once a simple collar had transitioned to become a potent symbol of status and wealth—the ultimate display of excess.

Marchesa Brigida Spinola Doria, 1606, Peter Paul Rubens, Public Domain via National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

England, Spain, and France went wild for lace creations with elaborate cutwork. Some of these designs became very complex.

For women, ruffs tended to be kept open at the front from the 1590s onward. For ceremonial occasions from the 1570s, unmarried women wore high, elaborate fan-shaped ruffs that were held in place with wires. These were rarely seen after 1615.

Frances Howard, dowager Countess of Kildare (c.1572 – 1628), later Baroness Cobham, between circa 1600 and circa 1601, Unknown, English School, Weiss Gallery, London, Public Domain via WikiCommons

Portrait of Margherita Gonzaga, Duchess of Lorraine (1591-1632), wife of Henry II, Duke of Lorraine, 16th century, Frans Pourbus the Younger, Museo Nacional de Bellas Artes, Buenos Aires, Public Domain via WikiCommons

In Holland, an undecorated version of the ruff was preferred, although the bigger the better. For a Dutch styled ruff one would need many meters of fine linen. The length ranged from 20-30 meters, which was then pleated tightly into hundreds of pleats.

Pictured below, on two different generations of women in the mid-17th century, we see a typical Dutch cartwheel ruff without the lace, although still quite elaborate.

While the ruff fell out of favor in the rest of Europe by the early 17th century, the ruff remained popular in Holland until the mid-to-late 1600s.

Portrait of Margaretha de Geer, 1661, Rembrandt, Public Domain via National Gallery London.

Portrait of a Bride, 1640, Johannes Cornelisz Verspronck, Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica, Rome, Public Domain via WikiCommons

Flanders took the happy medium and combined lace and linen, piled up into layers, making the collars look like huge wedding cakes as seen here.

Mother and child, 1624, Cornelis de Vos, National Gallery of Victoria, Public Domain via WIkiCommons

Portrait of a Lady, 1628, Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt, The Wallace Collection, Public Domain via WIkiCommons

Because ruffs had such social prestige, not wearing one was, in a way, taboo. Men and women wore ruffs whenever they went out, even dressing their children in them for a simple trip to market.

Bianca degli Utili Maselli and Six of Her Children, before 1614, Lavinia Fontana, Sotheby’s, Public Domain via WikiCommons

There are very few ruffs still in existence.

Here’s one on display at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

Irregularly wavy linen batiste pleated collar, consisting of a long strip pleated to a linen collar with a small stitch-stitch edge decoration, marked with cross-stitch in red silk 'CY', anonymous, c. 1615 - c. 1635, Public Domain via Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

After the ruff collar reached it’s zenith in the mid-to-late 1600s, it gave way to the “fallen ruff,” in which pleats were attached to the neckline of a garment and allowed to hang over one's shoulders rather than stand up. This style had always been common with men, but women began to wear them as well. In time, this style evolved into even more understated neckwear such as jabots and cravats.

Portrait of a Woman with a Lace Collarca, c.1632–35, Michiel Jansz. van Mierevelt, Public Domain via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

The Laughing Cavalier. 1624, Frans Hals, The Wallace Collection, London, Public Domain via WikiCommons

Modern fashion designers continue to be intrigued with Renaissance fashion and the ruff. Design houses such as Alexander McQueen, Christian Dior, Valentino, Chanel, Galliano, and Vivienne Westwood have all referenced the neckpiece.

Here’s a look at some ruffs, past and present.