Hidden Gems: 5 Major Artworks With More Than Meets the Eye

By Heather Bolen

Photo by author.

This summer, I had the opportunity to visit Rijksmuseum, one of my favorite museums in the world. As ex-pats in Amsterdam a number of years ago, we lived right on the grassy square in front of the museum, which we enjoyed like our own backyard. Living in such proximity to the museum meant it was easy to dip in and out, to explore in small doses. I often brought my laptop in the morning, just to work in the stark, but sun-filled café. A day browsing its grand galleries is always first on my to-do list when returning to this picturesque city.

Of course, Rembrandt’s The Night Watch is a must-see at the Rijks, and it’s hard to miss at 11′ 11″ x 14′ 4″.

It’s even harder to miss with Operation Night Watch underway.

The Rijksmuseum continually monitors the condition of The Night Watch, and museum conservationists recently discovered that changes are occurring, such as blanching on the dog figure at the lower right of the painting. To gain a better understanding of its condition as a whole, the decision was made to conduct a thorough examination: Operation Night Watch.

After a two-year investigation of the front, the painting has now been pushed out to examine the back and the canvas support of the painting. Through November 23, visitors can also see the back of the painting. In this video, take a peek behind the painting and behind the scenes as the Rijksmuseum moves the enormous masterpiece. The video gives an overview of the fascinating work they are doing to determine the health of the painting and the canvas.

Meanwhile, just outside the gallery where the original painting resides, the museum is repainting the piece in its entirety with the same elements Rembrandt would have used (see above).

This detailed study is necessary to determine the best treatment plan and will involve imaging techniques, high-resolution photography, and highly advanced computer analysis. Using these and other methods, they will be able to form a very detailed picture of the painting – not only of the painted surface, but of each and every layer, from varnish to canvas.

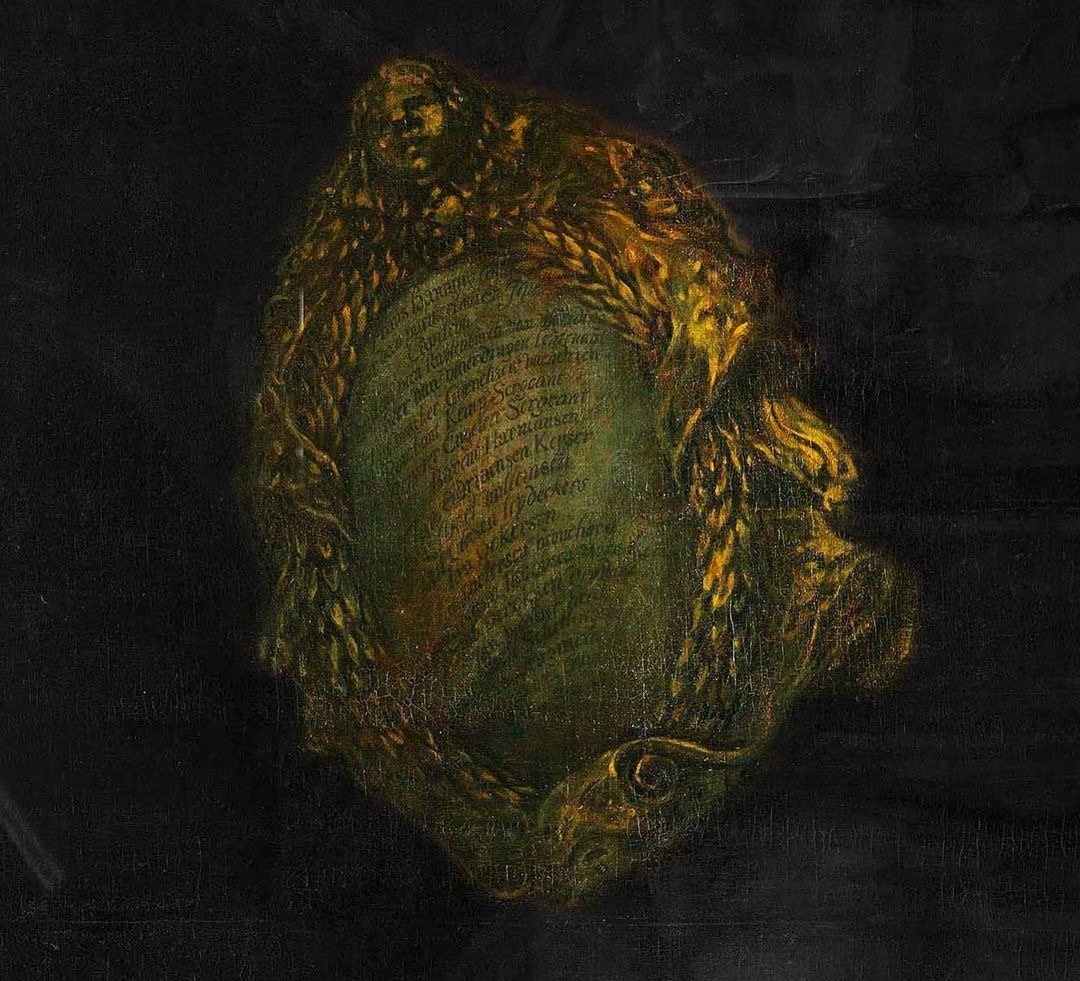

For example, Rembrandt did not paint the whole militia company of District II on The Night Watch, only those who could afford to pay for it. We know the names of these paying militiamen because they are listed on a shield that was added shortly after Rembrandt had finished the painting. However, the darkening of the old varnish had rendered the names unreadable by the eighteenth century. In 1947, after the discolored layers of varnish of the previous centuries had been removed, all the names emerged from the obscurity of ages. As part of Operation Night Watch, extensive research of the shield will be conducted.

The Rijks was positively aflutter during my visit, and all of the excitement got me curious about the technology used to examine such sensitive works of art.

Art conservationists commonly use x-ray technology for technical examination of paintings in order to assess their condition and learn about the original materials and techniques used by artists. Electromagnetic radiation is non-destructive and can pass through paint layers quite easily.

X-radiography is very useful for detecting composition changes, hidden paintings, and over-painted areas. This examination technique can reveal information about the composition and condition of the painting canvases, panels, wooden sculptures, the location, extent, and nature of damages like tears, holes, internal cracks, pest infestation, and also old repairs like inlays, fabric patches, linings and fills.

Fine Art Conservation notes “information collected by X-ray examination is extremely valuable to conservators as it helps to determine the conservation issues of the object and subsequent correct conservation approach. The information revealed by this type of examination can also assist art historians in the interpretation of the artwork and more specific dating.”

In 2008, Dutch scientist, Joris Dik (Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands), and his colleagues pioneered a new technique based on "synchrotron radiation-induced X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy,” known as macro-XRF, which measures the chemicals in pigments and accurately determine the original pigments of the hidden painting. Specifically, with the use of X-ray radiation, scientists excited elements to fluoresce, including calcium, iron, mercury, and lead.

This technology revolutionized the industry and only continues to get better. Nowadays, the scan can reveal the different crystalline structures of pigments at an atomic level, which enables the researchers to distinguish between the various pigments. For example, they could not tell the difference between various types of lead white. They merely revealed the presence of lead. The latest technique, called macro-XRPD, can do more than that.

What’s more, the technology is now portable. Early on, macro-XRF analysis had to take place in a laboratory with small fragments of paint or by relocating a painting, a risky and challenging endeavor. With the invention of a mobile scanner, the entire artwork can be examined at the museum or location where it resides.

The following five paintings illustrate the extraordinary possibilities of x-ray technology in art history and art conservation, including the secret paintings lurking beneath the surface.

01 | Picasso’s Old Guitarist (1903)

Pablo Picasso, The Old Guitarist, 1903, Art Institute of Chicago (Public Domain via Wikipedia)

In the case of Picasso’s 1903 painting, The Old Guitarist, the most iconic painting of artist’s “Blue Period,” an under-composition is actually visible to the naked eye.

Take a close look, and you will be able to discern the outline of a woman in the top center of the painting, near the old man’s neck.

Partial grazing light image of Picasso’s The Old Guitarist as it hangs at The Art Institute of Chicago

In 1998, The Art Institute of Chicago took a closer look at this painting using only a standard infrared camera and x-ray, and were able to penetrate the uppermost layer of paint (the composition of The Old Guitarist) to reveal the second-most composition in full. The researchers discovered a young mother seated in the center of the composition, reaching out with her left arm to her kneeling child at her right, and a calf or sheep on the mother's left side, along with an old woman with her head bent forward. Clearly defined, the young woman has long, flowing dark hair and a thoughtful expression.

Infrared reflectogram of The Old Guitarist (Art Institute of Chicago)

Christina, of the blog, Daydream Tourist, highlighted the unique elements that are visible in the higher resolution infrared and x-ray images:

Image Credit: Daydream Tourist

Image Credit: Daydream Tourist

The Art Institute of Chicago later collaborated with the Cleveland Museum of Art, where the curator identified a sketch by Picasso that he’d sent to a friend with the same composition of mother and child. However, the reason Picasso did not complete the composition with a mother and child, and how the older woman fitted into the history of the canvas, remain unknown. Artists commonly reused canvases, often because they didn’t have enough money to buy new canvases. At the time Picasso painted The Old Guitarist, he was living in poverty and emotional turmoil, yet the change in composition remains a mystery.

02| Van Gogh’s Patch of Grass (1887)

Patch of Grass was painted by Van Gogh in Paris in 1887. Behind the painting is a portrait of a woman. (Image credit: TU Delft)

Van Gogh was known to paint over his work to save money, perhaps as much as a third of the time. Experts assumed they’d find something under any number of Van Gogh’s works. X-ray studies using standard technology, however, like the kind that uncovered a clear image of the under-composition in Picasso’s Old Guitarist, only revealed a faint, blurry shadow of a figure underneath Van Gogh’s Patch of Grass.

With knowledge something was hidden beneath the vibrant greens and blues, the painting was one of the first to be analyzed by the new macro-XRF technology when it debuted in 2008. Again, this new technique measures the chemicals in pigments. In this case, mercury and the element antimony were useful in revealing a woman's face painted in much darker brown and red tones.

Patch of Grass was painted by Van Gogh in Paris in 1887 and is owned by the Kröller-Müller Museum. The reconstruction enabled art historians to understand the evolution of Van Gogh’s work better, the researchers said in a statement.

What is significant about the discovery of the face is it shows the rapid evolution of his style and use of colour, as the two layers are estimated to be only painted two-and-a-half years apart, with Patch of Grass dated to 1887.

In late 1884, Van Gogh painted a series of heads of peasant models in their homes as a means of training his control over color and light, and the woman discovered beneath Patch of Grass is likely part of this series. According to Nature.com, Dik's team speculates that Van Gogh took the portrait with him to Paris, “where it would have seemed sombre and unfashionable in comparison to the Impressionists' works, and so he decided to paint a brighter, more commercial floral scene over it.”

03| Rembrandt’s An Old Man in Military Costume (1630-31)

Half-finished mock-up of Rembrandt's "Old Man in Military Costume," with a portrait painted underneath the final work (Image credit: Andrea Sartorius, © J. Paul Getty Trust)

This same new X-ray technology that debuted in 2008 uncovered one of the most famous art-historical mysteries of all time.

Since 1968, art historians and scientists have known a secret painting existed beneath Rembrandt’s 380-year-old masterpiece, Old Man in Military Costume. They’d probed the painting with infrared, neutron, and conventional X-ray methods, but could not see the behind the top coat because Rembrandt used the same paint (with the same chemical composition) for the underpainting and the final version. They could only detect the faint traces of another portrait.

In 2013, worried about relocating the painting from the Getty Museum where it resides, an international team of scientists did two things in order to examine Old Man in Military Costume. First, they created a full mock-up of the painting (see image above), which allowed the team to test out different methods of looking beneath the original painting. Museum graduate intern, Andrea Sartorius, created the detailed mock-up using paint with the same chemical composition as used by Rembrandt and painted two pictures on the same canvas: a portrait and on top of it a replica of the Old Man in Military Costume.

Secondly, the team bombarded the mock-up with high-energy X-rays (macro-XRF or MA-XRF) to reveal the different pigments.

In a statement, scientist, Karen Trentelman of the Getty Conservation Institute, said:

The successful completion of these preliminary investigations on the mock-up painting was an important first step. The results of these studies will enable us determine the best possible approach to employ in our planned upcoming study of the real Rembrandt painting.

X-radiographs of An Old Man in Military Costume. The X-ray at right is inverted to better show the hidden painting. (Image Credit: J. Paul Getty Museum)

This is what the team found:

White is present in areas containing lead, used in Rembrandt’s time to make a creamy white paint.

Red can be reconstructed where we find mercury, present in the scarlet pigment vermillion.

Blues and greens are likely where we see copper, a component of pigments such as azurite and copper resinate.

Earth tones from umber pigments are present in areas containing both iron and manganese.

Put together, this adds up to a man with brownish hair, with a collar (perhaps a metal gorget) and an olive cloak as depicted in the image below. (The line through the face is a shadow from the strong contour of the beret in the painting of the old man above.)

Tentative color reconstruction of the hidden portrait under An Old Man in Military Costume. (Image Credit: J. Paul Getty Museum)

The team still has much work to do as the second layer is so thick as to still obscure a full view of the portrait underneath. The next step, of course, is to repeat the process on the real thing.

04| Unknown Artist, Queen Elizabeth I, (c.1558)

In this example, recent X-ray analysis has revealed another complete image of Queen Elizabeth beneath this 1558–1561 portrait published by London’s Philip Mould & Company.

The portrait underneath remains largely intact. In it, Elizabeth’s costume appears to be much more flamboyant with a larger ruff and elaborate padded sleeves visible.

Oak panels were imported from the Baltic region and costly, so it was not uncommon for panels to be recycled and updated with a subject’s latest likeness. This was also the case for Rembrandt’s painting, Old Man in Military Costume, discussed above.

The curators at Philip Mould & Company note we may never know for certain the reason for these adjustments. However, they propose the initial portrait may have been judged improper during Elizabeth’s early reign when the young queen was better served by a more restrained look. Later, of course, Elizabeth mastered the use of portraiture for self-promotion and ostentatious depictions of herself.

Video Credit: Philip Mould & Company

05| Jacques-Louis David’s Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743–1794) and Marie Anne Lavoisier (Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze, 1758–1836) (1788)

Antoine Laurent Lavoisier (1743–1794) and Marie Anne Lavoisier (Marie Anne Pierrette Paulze, 1758–1836), Jacques Louis David, 1788 | Public Domain via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

If you’ve been to the Met, then you have likely encountered this monumental painting by Jacques-Louis David. It is exceptional not only for its size (nearly nine feet high by six feet wide) but because it’s also considered by many to be the best neoclassical portrait in the world.

The painting depicts Antoine Laurent Lavoisier, the “father of modern chemistry” and his wife, Marie Anne Lavoisier. Lavoisier was a gifted scientist, noted for a number of major contributions to science, including the metric system, the first table of elements, and the discovery of oxygen and hydrogen. In the painting, he is seen working on his important manuscript in chemistry that he published soon afterward. Madame Lavoisier collaborated with her husband in his experiments and their close relationship is noticeable in the painting. She was an artist in her own right, having studied under Jacques-Louis David, himself, and created illustrations and diagrams for her husband’s book. In the background of the painting, you can see a portfolio of her artwork. Experts suggest that the artist wished to show the marriage of art and science through his two subjects.

Recently, in 2017, the painting underwent a careful examination and conservation effort for the first time since its arrival at The Met in 1977. While removing a degraded synthetic varnish on the painting’s surface, the museum conservator noticed points of red paint showing through, particularly at Madame Lavoisier’s head and dress as well as the tablecloth. This discovery led to a three-year examination of the painting employing macro X-ray fluorescence imaging (MA-XRF) to map out the distribution of elements in the paint pigments—including the paint used below the surface.

Jacques-Louis David’s 1788 painting of Antoine and Marie-Anne Lavoisier (Department of Scientific Research and Department of Paintings Conservation, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; originally published in Heritage Science)

It turns out, during the French Revolution, the original painting was completely reworked to present the couple as modern, progressive, and scientifically-minded, and intentionally conceal their identity as wealthy, privileged, fashionable tax collectors.

Indeed, beneath the austere background, Madame Lavoisier had first been depicted wearing an enormous hat decorated with ribbons and artificial flowers. The Costume Institute traced the hat design to a style called chapeau à la Tarare, popular in the summer and fall of 1787, when Jacques-Louis David likely began the portrait (see below). Other fashion plates indicate that belts and ribbons typically coordinated with the hat set against the simple linen of the dress, known as a chemise à la reine. Elsewhere in the underpainting, the red tablecloth was once draped over a desk decorated in gilt bronze, and most significantly, the scientific instruments were missing and added later.

Magasin des Modes Nouvelles Françaises et Anglaises, 10 novembre 1787, 36e cahier, 2e année, Pl. 1, A.B. Duhamel, after Defraine, 1787, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Due to the political climate of the time, David wasn’t even able to display it at the Paris Salon for fear of public backlash. He likely reworked the painting quickly, but the effort did not save Monsieur Lavoisier. Lavoisier was firmly entrenched in France’s Ancien Régime, the dominant system of rule upended by the revolution in the last decade of the 18th century. During that period, he was arrested for his complicity as a tax collector and sent to the guillotine during the Reign of Terror.

In a statement, Max Hollein, director of the Met said:

The revelations about Jacques-Louis David’s painting completely transform our understanding of the centuries-old masterpiece,” said Max Hollein, director of the Met, in a statement. “More than 40 years after the work first entered the museum’s collection, it is thrilling to gain new insights into the artist’s creative process and the painting’s evolution.

Hats off to science!

#TravelandCultureSalon

FOLLOW @TRAVELANDCUTLURESALON ON INSTAGRAM